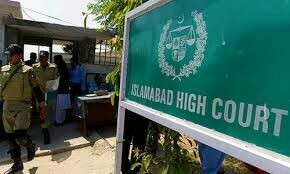

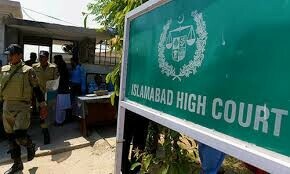

ISLAMABAD: As the constitutional bench (CB) of the Supreme Court on Monday took up a set of review pleas against the top court’s ruling that had declared the PTI eligible for reserved seats, two judges declared the petitions as inadmissible.

In its July 12, 2024 short order, eight out of 13 judges ruled that 39 out of a list of 80 MNAs were and are the returned candidates of the PTI, setting it to emerge as the single largest party in the National Assembly.

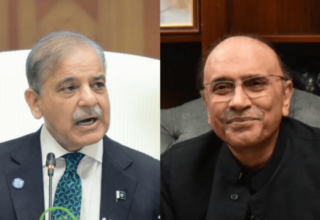

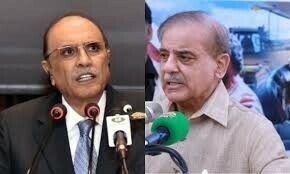

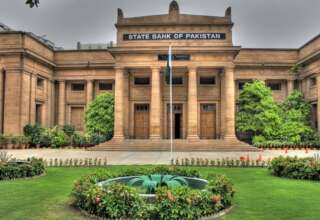

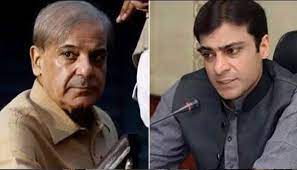

However, the ruling had not been implemented by the National Assembly, while the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) had raised some objections. The review petitions against the SC order had been filed by the PML-N, the PPP and the ECP.

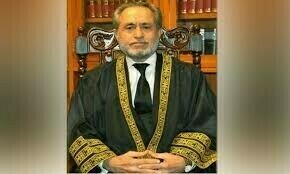

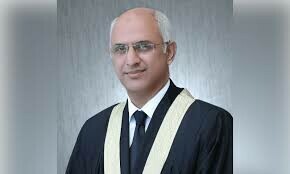

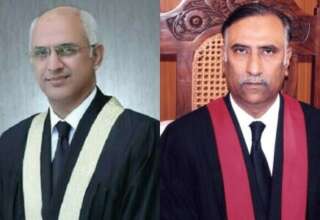

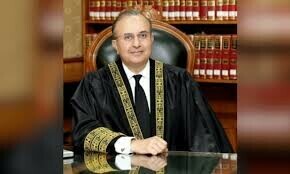

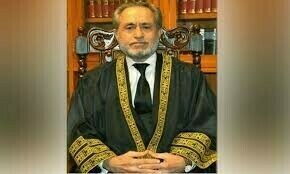

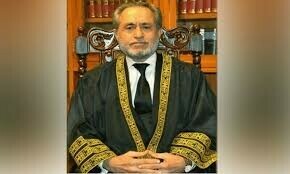

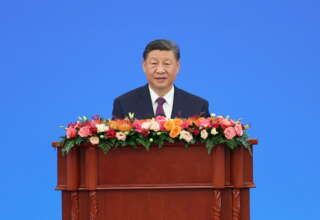

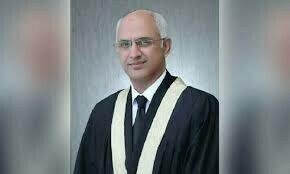

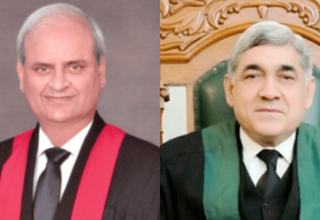

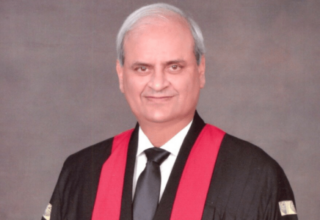

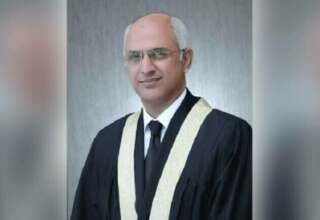

As the full-strength 13-member CB led by Justice Aminuddin Khan took up the review pleas today, Justices Ayesha A. Malik and Aqeel Ahmed Abbasi objected to them, declaring the applications as inadmissible.

The other 10 members of the bench were Justices Jamal Khan Mandokhail, Muhammad Ali Mazhar, Syed Hasan Azhar Rizvi, Musarrat Hilali, Naeem Akhter Afghan, Shahid Bilal Hassan, Muhammad Hashim Khan Kakar, Salahuddin Panhwar, Aamer Farooq and Ali Baqar Najafi.

Five of the eight judges who ruled in PTI’s favour — namely senior puisne judge Justice Mansoor Ali Shah, Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Athar Minallah, Justice Shahid Waheed and Justice Irfan Saadat Khan — are not part of the CB.

While Justices Mazhar, Ayesha and Rizvi were part of that majority verdict, Justices Aminuddin and Afghan had rejected the PTI’s pleas, denying it the reserved seats.

According to a cause list issued by the SC, the review pleas included three filed by the PML-N, including one by its leader Huma Akhtar Chughtai, as well two each from the PPP and the ECP.

Barrister Haris Azmat appeared as the counsel for the PML-N while Sikandar Bashir Mohmand was present on behalf of the ECP.

During the hearing, judges of the apex court repeatedly questioned the ECP lawyer about the electoral watchdog not implementing the July 12 verdict.

While the CB formally accepted the review petitions for hearing, Justices Ayesha and Abbasi dissented with the majority decision, objecting to the maintainability of the pleas.

With a split majority of 11-2, the bench issued notices to the parties in the case and adjourned the hearing till tomorrow (Wednesday).

It also stated that a contempt plea filed by PTI’s Kanwal Shauzab against the ECP for not implementing the SC’s July 12 ruling would be clubbed with the review pleas.

In its review application, the ECP submitted that the July 12 short order was based on the law that has since been altered by the amendments made to Sections 66 and 104 of the Elections Act and a new section, namely 104-A, has also been inserted with retrospective effect.

It requested the SC to revisit its judgement in the reserved seat case that granted relief to the PTI, saying it was neither a political party nor individuals claiming to be its candidates had ever approached the ECP, Peshawar High Court or the apex court to claim the reserved seats.

In its detailed verdict on the reserved seats case, which was authored by senior puisne judge Justice Mansoor Ali Shah, the SC had observed that the ECP’s numerous “unlawful acts and omissions” had “caused confusion and prejudice to PTI, its candidates and the electorate who voted for PTI”.

It had also castigated the ECP for failing to fulfil its “role as a guarantor institution and impartial steward” of electoral processes.

On Sept 14, 2024 — the day the government was supposed to lay the 26th Amendment in both Houses of the parliament but could not — the Supreme Court, through a clarification, had reprimanded the ECP for not implementing its July 12 ruling in the reserved seats case.

Later on October 18, in yet another clarification, Justice Shah reiterated that the effect of an amendment made in the Elections Act 2017 in August last year could not undo the reserved seats case verdict.

The bill, titled “Elections (Second Amendment) Act, 2024”, was seen as aimed at circumventing the apex court’s verdict on the reserved seats case by barring independent lawmakers from joining a political party after a stipulated period.

A six-judge CB of the apex court was set to take up the PTI’s petition challenging those tweaks to the election laws in December 2024. A separate plea of the PTI against the Jan 13, 2024 ruling denying it its election symbol is also pending before the SC.

The hearing

At the outset of the hearing, PML-N lawyer Azmat contended that the reserved seats were allotted to a political party that was not a respondent in the case.

He was referring to the PTI which was not a party to the case, but instead, the Sunni Ittehad Council, with which it had allied for the elections, was a respondent.

Justice Ayesha then replied that this question had been asnwered in the detailed verdict. “What is the basis of your review petition?” she asked.

Responding to Justice Mazhar’s question that whether the PML-N disagreed with the entire ruling or only the majority ruling, the lawyer replied that he was objecting to the majority ruling only.

Justice Ayesha observed that the scope of review was limited and arguments could not be presented twice in a case. Justice Mandokhail also noted that the orders of the returning officers (ROs) and the ECP were available, to which Azmat responded that the PTI did not challenge those orders despite having “an army” of lawyers in the party.

“Will we punish the nation for the mistake of a party? Could we let go of a matter if it came to the notice of the Supreme Court?” Justice Mandokhail asked. Justice Ayesha, who was part of the original ruling, stressed that the judges had arrived at the decision after hearing all “points in detail”.

Addressing the PML-N lawyer, Justice Abbasi remarked: “You keep mentioning political party. Leave that aside. The Supreme Court gave its decision according to the Constitution. Tell us what the mistake in the judgment was.

“We know the things you are telling us from our student days. Would you now teach the Supreme Court?” the judge added, ordering Azmat to argue on the grounds for the review instead of repeating arguments on the original case.

Here, Justice Ayesha Malik asked whether the reserved seats verdict was implemented, to which Azmat replied that he was not sure about it. “You are standing before the court. What does this mean that it is not confirmed to you?” she asked.

Justice Ayesha also wondered how a review plea could be filed without the earlier order being implemented. Justice Mandokhail said: “You (Azmat) also have to tell whether the ECP is not bound to implement our orders.”

Adding to this, Justice Abbasi pointed out that a contempt plea was also before the court over the non-implementation of the July 12 court order.

At this point during the hearing, Mohmand, the ECP’s counsel, came to the rostrum. Justice Kakar asked the lawyer to respond in a “yes or no” about whether the SC ruling had been acted upon.

Upon Mohmand replying that the electoral watchdog had followed the order “to the extent of one paragraph”, Justice Abbasi remarked: “Is it up to your wishes that which paragraph you choose to implement?”

Justice Ayesha then inquired of Azmat how the ECP was an affected party in the case, questioning how it could seek review of something it had not implemented. “Your job is to hold elections. How can you become a party to this case?”

To this, Mohmand responded that the PHC had made the ECP a party. Justice Ayesha quipped: “The Supreme Court interpreted the Constitution [but] you did not like that interpretation, so you came to the SC again.”

Justice Kakar then remarked, “If the ECP has implemented the [earlier] order, then it is fine. Otherwise, what guarantee is there that our order will be implemented?”

Mohmand informed the judge that the ECP had followed that ruling “partially”, at which Justice Ayesha observed, “You cannot pick and choose which orders to follow. You implemented the bits you liked and did not implement what you did not like.”

Addressing the ECP lawyer, Justice Abbasi suggested taking up the contempt plea against the commission that was pending. “If the contempt proceedings against you are heard, will you [still] seek a review?”

Mohmand then insisted that the ECP had followed the court orders, at which Justice Abbasi told him not to say so as it was not the case.

Here, Justice Mandokhail remarked, “In which direction are you taking the Supreme Court? If someone is sentenced to death tomorrow, will they say that the noose was only put up to their head and left there?”

Justice Ayesha observed that she had a question on the maintainability of the ECP’s review petition, while Justice Abbasi asked the lawyer if he would be able to present arguments in the contempt case if that was taken up.

Subsequently, with an 11-2 split — as Justice Ayesha and Justice Abbasi objected to the admissibility of the pleas — the CB issued notices to the parties and adjourned the hearing till tomorrow.

‘Clear error in verdict must be identified for review plea to be taken up’

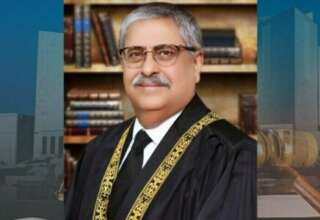

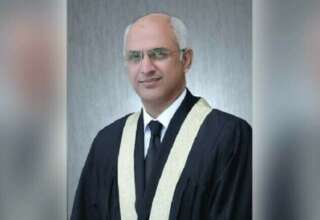

Earlier today, a three-member bench of the SC observed that a “clear error” in an original verdict must be identified for a review petition to be accepted for hearing.

The ruling came as the bench — led by Justice Shah and comprising Justices Mazhar and Hassan — took up a set of civil review petitions against a PHC ruling which had dismissed challenges brought by candidates who had been denied appointments as primary school teachers.

Justices Mazhar and Hasan are part of the CB that has taken up the review pleas against the SC’s ruling on the reserved seats case.

The judgment, authored by Justice Shah, stated that a review could be sought only under Article 188 of the Constitution, which empowers the SC to review any judgment pronounced or order made by it, or under the Supreme Court Rules of 1980.

Citing the Code of Civil Procedure 1908, the order stressed that “some mistake or error apparent on the face of the record” was one of the situations where a review may be sought.

Acknowledging that the phrase “cannot be defined with precision”, Justice Shah declared that the error “must be self-evident, immediately apparent, and not require extensive discussion or reasoning”.

The power of review was “not an open invitation to revisit judgements merely on the basis of dissatisfaction with the outcome”, the judge emphasised.

“A decision, order, or judgment cannot be corrected simply because it is erroneous in law, or because a different view could have been taken by the court or tribunal on a point of law or fact,” he noted.

“Frivolous claims serve no purpose other than to waste the court’s time and resources,” the order stated, clarifying that the power of review should not be confused with the appellate power.

Noting that there were over 2.2 million cases currently pending before courts across Pakistan, including approximately 56,635 before the SC, the ruling pointed out that “frivolous, vexatious and speculative litigation contributes substantially to this backlog”.